Digital procurement promises that it will rescue us from the tedious bureaucracy, the pre-occupation with cost over risk-adjusted value, distortions stemming from the pro forma attempts at gaming the compliance regime, and the adversarial relationship between buyers and suppliers.

Here’s US Air Force Major General Cameron Holt, deputy assistant secretary for contracting talking about this moment in procurement:

“On the other side of the coin, I see a renaissance going on. I see people tired of being told ‘no.’ People being tired of all the red tape, a real weariness of overly prescriptive items, and a vastly long time frame and risk averse approaches to contracting …”

We would expect the Department of Defense to be bureaucratic. But this comment is probably more representative than we would like.

Efforts to improve continue but with disappointing progress to show for it. With full credit for their persistence, the UK government this week heralded the latest plans (of many over the years) to traverse the administrative morass:

“Today’s measures will transform the current procurement regime to put value for money at the heart of the new approach, by allowing more flexibility for buyers, enabling government to be more strategic and save the taxpayer money. This will also drive increased competition through much simpler procurement procedures.” [emphasis added]

The private sector is no better. Survey after consulting firm survey shows that digital transformation of procurement continues to underwhelm.

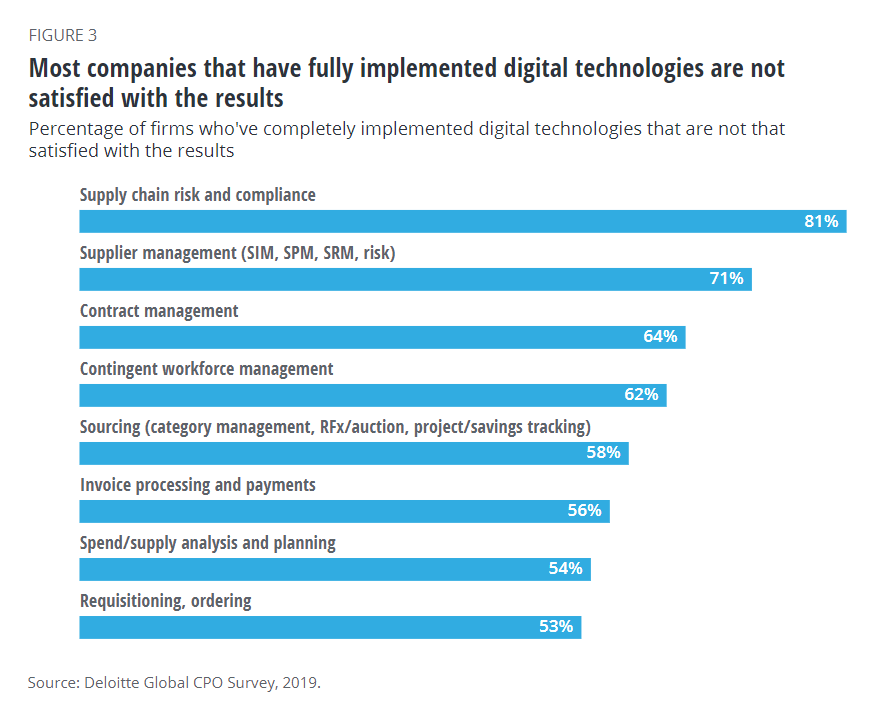

For example, looking at the Deloitte Chief Procurement Officer Survey of 2019 (abstracting from the implications of the Pandemic), they report general dissatisfaction with the results.

Why hasn’t digital procurement delivered us from this pain and suffering?

The theme of the Deloitte survey is “complexity.” The purpose of the technology shift is to reduce “bad complexity” and to increase “good complexity.” Bad complexity “introduces risk and hampers procurement” while good complexity extends the reach of the procurement department “to more broadly influence business stakeholders in strategic areas (e.g., capital expenditures, enterprise risk management), as well as more deeply influence stakeholders through demonstrated leadership in areas such as corporate development.”

The iatrogenic effect of introducing most of the technology to date, we are told, has been to unleash new forms of complexity, even as it chips away at improving the mix of antecedent bad complexity and good complexity.

But what if there is a deeper, more fundamental problem at work? What if the usual explanations for the conventional dissatisfaction are inadequate in addressing the root issues?

Let’s start with Bill Gates’ two rules for enterprise software:

“The first rule of any technology used in a business is that automation applied to an efficient operation will magnify the efficiency. The second is that automation applied to an inefficient operation will magnify the inefficiency.”

This is amplified by another general rule of digital transformation, this time from Stratechery’s Ben Thompson:

“When it comes to designing products, a pattern you see repeatedly is copying what came before, poorly, and only later creating something native to the medium.”

The leading contemporary procurement systems, especially the ERP modules and cloud-based source-to-pay systems, have taken the analog sourcing process and coded it up. Recently, a big trend has been the improvement in the user experience, making the systems marginally easier to use. They are still poorly designed for the most part, cumbersome kluges of functionality. They’re just kluges that are marginally easier to use.

There has been no substantive change to the sourcing business process to take advantage of the digital environment. If anything, current and prior generations of procurement software actually lock buyers into the weakness of the old business process.

Thompson uses the example of social networking to explain his rule.

In the beginning, individuals had real personal networks of friends and family whom they would see or call directly. Facebook digitized these personal networks. It was a stronger player for having more friends and family in the same online location. The conversation now taking place in something Facebook called a “feed.” Individuals would broadcast their speech to a single group: their followers. The content in these individual speech snippets appealed to different subsets of the group. For example, a comment about a sports team might not appeal to your mother as much as a copy of a photo of your daughters playing soccer, but it might speak to your friends from college.

There was only so much value one could obtain from conversations with those in a personal network, so Facebook added professionally created content published by others. This kept engagement high.

Newspapers similarly replicated their business when they first went online by posting their physical newspaper’s stories, locating general advertisements alongside them. This had little economic traction.

However, the introduction of the feed introduced the ability to personalize the content the publisher could serve to the individual and, with it, ads customized for the consumer, as well. This was much more lucrative.

Other types of social networks appeared. Twitter meant “broadcasting conversations as if you were sitting in a bar.” That is, you would be talking to people who were not necessarily in your physical network, but in a new general network of acquaintances you met online. Again, people with broad interests make comments that appeal to different subsets of their group.

Note that there is tremendous pressure to appeal to everyone who follows you. If you have many subsets given the variety of your interests, you dilute your traction. If you only speak on one topic, you are more likely to concentrate a strong followership.

Thompson descries this inability to segment the profile as leading to the breakdown of the conversation in these networks, saying that Twitter has “grown too noisy, performative, and combative to be a place to simply hang out …”

Social networks are evolving. Witness the explosive growth of TikTok, for example. TikTok does two things differently:

“ByteDance’s 2016 launch of Douyin – the Chinese version of TikTok – revealed another, even more important benefit to relying purely on the algorithm: by expanding the library of available video from those made by your network to any video made by anyone on the service, Douyin/TikTok leverages the sheer scale of user-generated content to generate far more compelling content than professionals could ever generate, and relies on its algorithms to ensure that users are only seeing the cream of the crop.”

Where Facebook’s content is developed by either one’s personal network or by professional publishers and Twitter’s content is developed by one’s contrived network-of-relative-strangers, TikTok’s content is developed by everyone on its entire network.

TikTok can do this because it learns what to send each user, training itself constantly on the preferences of the individual.

How does any of this apply to procurement?

In a real sense, the procurement process is centered around content. Buyers issue RFPs or RFQs in which they describe their problem and what they’re looking to buy, as well as the rules around how they will execute the acquisition. Suppliers respond with proposals in which they lay out who they are and what they offer.

The buyers are looking for value for money and for that they need to drive competition, as the British noted above. Competition comes in the form of more proposals from a broader array of suppliers, spanning a diverse set of solutions and price points.

To borrow Thompson’s terminology, Procurement v1 involves porting a real-life network into a digital solution.

In Procurement v1, the digital business process is unchanged from its analog predecessor.

Just as Facebook puts our friends and family into our group online, Procurement v1 solutions give us a virtual environment where buyers and suppliers exchange content. That is, buyers only solicit suppliers who are already set up as vendors-of-record after going through a months-long (or longer) vetting process.

In Procurement v1, suppliers only see the RFPs/RFQs that buyers send to them, typically by email. If a buyer thinks a supplier makes widget X, they will send them an RFP every time the buyer is in the market for X. If a buyer thinks a supplier does not make widget Y, they will never send them a copy of the RFP when the buyer is in the market for Y.

This assumes that the buyer knows accurately what the supplier does and keeps track of this over time. Suppliers complain routinely that they do not see relevant RFPs because buyers don’t know the supplier is in the market.

Procurement v2 adapts the business process to exploit the flexibility that the digital approach permits.

As with TikTok, buyers in Procurement v2 will solicit every supplier for the good or service they seek to purchase, regardless of their antecedent status as a vendor-of-record. As with TikTok, suppliers will see all of the RFPs/RFQs relevant to their vertical categories. They will not miss any opportunities because the buyer didn’t know they were in the market.

Let’s say the buyer is in the market for trucks.

To be able to solicit all the buyers of trucks, the buyer will need to be able to thoroughly vet and onboard a supplier in a matter of days, should they pick a new supplier as having the best bid. This requires rapid access to standardized due diligence materials and customer referrals.

To permit efficient solicitation of all the buyers of trucks, there needs to be a platform that can effect this matching and redundantly provide a space for truck vendors to find the relevant RFP with sufficient time to craft a responsive proposal.

Another point that Thompson discusses is messaging. Messaging permits people to segment groups into those that speak to different aspects of their personality. For example, an investor may also have an interest in finance, sports and correctional reform. Tweeting about all three topics can be distracting and confusing, costing him followers. Instead, being in separate sub-groups for each of these topics may make more sense.

“Even that, though, suggests that the company can’t entirely escape its roots: having one identity is a core principle of Facebook, which is great for advertising if nothing else, but at odds with the desire of many to be different parts of themselves to different people in different contexts.”

Messaging will be the place in which the substantive, specific discussions take place among members of self-selected sub-groups.

In Procurement v2, there needs to be a channel for these kinds of collaboration to take place. Buyers need to talk to other buyers for information and market intelligence. Suppliers need to speak with one another about business development. Buyers and suppliers need to speak with one another to get a better understanding of the marketplace. All of which needs to happen in the context of different, possibly overlapping, vertical categories.

“On the flipside, to the extent that v2 social networking allows people to be themselves in all the different ways they wish to be, the more likely it is they become close to people who see other parts of the world in ways that differ from their own. Critically, though, unlike Facebook or Twitter, that exposure happens in an environment of trust that encourages understanding, not posturing.”

Wouldn’t understanding, not posturing, in procurement v2 be a wonderful thing? It would help people get to product-solution fit much faster, without the overhead of distortions and a contrived sense of adversarial opposition.

EdgeworthBox was built for Procurement v2.

We sit as a layer in the procurement technology stack to augment the existing approach to RFPs/RFXs. We do this by adding proven tools from financial markets to whatever you are using currently. These include central clearing of vendor administration and data, as well as social networking.

With EdgeworthBox, buyers can onboard new vendors rapidly, enabling the solicitation of suppliers who have no antecedent vendor-of-record relationship. We have public and private repositories of structured data of live and historic RFPs and historic contract data for market intelligence and speedier RFP cycles. Our social networking functions include profile pages for advertising organizations and individuals, as well as a messaging platform that connects buyers to buyers, suppliers to suppliers, and buyers to suppliers. Suppliers join for free. Buyers pay an organization license with unlimited seat licenses. Give us a shout or take us for a free trial.