Peter Thiel wrote the book on entrepreneurship: Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future, In it, he talks about the principles that he believes work well for people looking to solve problems.

For him, there is one question that can help him understand the potential employees or the founders of companies in which he might invest.

What important truth do very few people agree with you on?

As Farnam Street highlights:

“This question sounds easy because it’s straightforward. Actually, it’s very hard to answer. It’s intellectually difficult because the knowledge that everyone is taught in school is by definition agreed upon. And it’s psychologically difficult because anyone trying to answer must say something she knows to be unpopular. Brilliant thinking is rare, but courage is in even shorter supply than genius.”

In highlighting what a good answer looks like, Thiel says:

“A good answer takes the following form: “Most people believe in x, but the truth is the opposite of x.””

What then are some things that most people say about strategic sourcing in the form of a reverse auction such as a Request for Proposal or Request for Quotation, or procurement writ large.

Here are some implicit beliefs we have observed in buy side behavior:

- Reverse auctions need to be bureaucratic exercises in compliance to ensure the minimization of fraud, waste, and abuse

- Suppliers will put up with a great deal to win the business

- Three bids are enough

- The supplier with the best presentation is the best supplier for the job

- Reverse auctions do not involve collaboration across organizations

- Procurement often does not require collaboration within organizations

The supply side has its own shibboleths:

- To win a reverse auction, it is vital to “shape” the RFP questions in one’s favor

- The buyer makes up his mind before the RFP in most cases

- Buyers don’t understand the category, even if they say they do

- The process is expensive for suppliers

- It is rare to see a well-written RFP questionnaire

If we were to summarize these beliefs into a single sentence, it might be: Most people believe that procurement has to be a cumbersome, expensive, prolonged administrative process.

Note that the emphasis is on the word “administrative” in that sentence.

What is the ultimate objective of procurement?

Buyers want to purchase the right solution, from the right supplier, at the right price. They may be buying something that will be part of their operation for years to come, or something that will have a meaningful impact on the value they themselves deliver to their own customers.

- The right solution: the good or service that has the best product-solution-fit

- The right supplier: the vendor with characteristics buyers deem necessary

- The right price: the lowest price that any other buyer pays for the solution in the market

There are tradeoffs at work, of course. The solution that has the best product-solution fit may not be the one with the lowest price compared to other solutions. Is it better to give up some performance for a lower price? Are we seeing a much lower price from a vendor because the vendor is unreliable? (We see this in IT services contracts frequently, for example.)

The best solution priced competitively coming from a supplier with whom we want a relationship is value-for-money..

It is intuitive that the more proposals the buyer sees from potential suppliers, the more likely the buyer is to home in on value.

For example, consider Acme Inc. They have a problem. Their internal conclusion is that they will need to buy something to solve this problem. The CFO convenes a committee of internal stakeholders. Their job is to purchase the solution. They come from different parts of the enterprise: engineering, product, finance, sales, marketing, etc.

Let’s assume that there are 100 companies out there with some version of a solution. Some of them are well-suited for Acme’s problems, others only incidentally so. Let’s say that there are 5 companies out of the 100 that have a really good problem-solution fit.

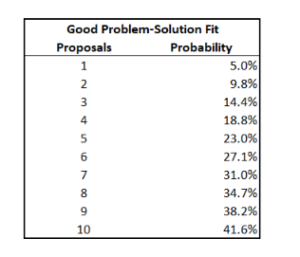

What are the chances that one of these 5 submit a proposal if there are only three suppliers that do respond in the reverse auction? As it turns out, it’s just over 14%.

(The probability of not seeing a good fit in the first proposal is 95 divided by 100. The probability of not picking a good fit in the second proposal is 94 divided by 99. The probability of not picking a good fit in the third proposal is 93 divided by 98. Subtracting the product of these three ratios from 1 leaves us with just over 14%.)

Now consider the probability of seeing a good proposal if we receive ten submissions: almost 42%.

With 25 proposals in-hand, the probability exceeds 77%.

Do the assumptions embedded within buyside behavior and technology systems likely deliver value-for-money? It’s hard to see how they could.

There are costs.

Buyers must spend money and time to flesh out their understanding of the problem they face, to learn about the different possible solutions they could purchase, to write a bid solicitation that attracts as many proposals as possible, to cajole suppliers into submitting proposals, and to evaluate the submissions they receive, all culminating in a joint committee decision spanning multiple internal groups. There are transactions costs associated with all of this. But there are also opportunity costs, especially for longer-term projects. If they pick solution A, but solution B would have delivered better performance, say in the form of lower costs over the lifetime of the project, then the difference in lifetime costs between A and B represents an opportunity cost they incur. Think of it as sub-par A delivering a lower return on investment than optimal B.

It’s safe to say that many buyers do not consider opportunity costs when they decide. They place a disproportionate emphasis on upfront costs and transactions costs. Savvy suppliers load the costs into the back in the same way that car dealers structure lease payments, sensitive to car buyers’ conflation of affordability with value.

Suppliers spend money too. When the supplier receives an RFP, they must decide whether to participate. There are myriad factors. Has the RFP been shaped by a competitor? What is the probability of winning? What is the size of the contract should they win? What is the margin should they win? How much time and money will it cost to develop the proposal? The best suppliers convene a committee of people from across the enterprise to decide whether or not to reply.

In both cases, buyers and suppliers make an investment decision.

The buyer’s committee of people from across the enterprise is an investment committee. It compares the different proposals to determine which one offers the best value-for-money. It wants to select the solution with the best return on investment.

The supplier committee decides whether to submit a proposal. There is the cost in time and money of putting something together weighed against the expected value of a deal: the probability of winning multiplied by the value in terms of profit or free cash flow of a successful bid.

Should the supplier invest in making a bid?

This is no different than the decisions made every day in capital markets by buyers and sellers of businesses or securities. When a company decides to consider strategic factors, they may hire an investment bank to auction the firm off. Portfolio managers at asset management companies and hedge funds and private equity shops evaluate companies for purchase or sale from their portfolios, often requiring a trip to the internal investment committee for large or controversial trades.

In both the procurement context and the financial context, these are investment decisions, distinct from consumption decisions.

A consumption decision is short-term. As an individual, I fill up my tank of gas today at the local as station and I use up the fuel as I drive around town. As a company, I might enter into a long-term arrangement to purchase fuel from a supplier where the price is tied to a benchmark and I am purchasing attendant services that will guarantee fuel availability through various conditions.

It is easy to see how purchasing equipment or software that I will use over the course of years to manufacture a product is an investment. I even capitalize the cost.

When we look at the tools that investors in financial markets use to manage their portfolio risk and to buy and sell securities, they are anything but “cumbersome, expensive, prolonged, administrative” processes.

There is an arms race in financial technology to execute simply, inexpensively, and immediately. A trader in NY pushes a button and she purchases 100,000 shares of IBM, with an efficient process for settling the trade two days later. In the US, we are moving to one day settlement of equity trades.

Here’s my answer to the Peter Thiel question when it comes to procurement:

Most people believe that procurement has to be a cumbersome, expensive, prolonged administrative process, but the truth is that procurement should be and can be an efficient, inexpensive, rapid investment process.

The way to bridge this gap is digital transformation of the business process, augmented by generative AI tools.

This is what we have built at EdgeworthBox: a set of tools, structured data, and community that enable B2B buyers to ensure they buy the right solution, from the right supplier, at the right price. It is simple and distinct. It is much easier to use across the breadth of the enterprise, accelerating the time to consensus and shortening the procurement cycle, while surfacing more competition on price and solution for better long-term economics. We’re working to leverage our domain expertise into generative AI solutions using the new Transformer foundational models. If you’d like to learn more, please shoot us a note.