When I talk to people with experience in financial markets about the RFP process, they shake their heads at the primitive nature of it all.

They are accustomed to speed, transparency, and efficiency. The New York Stock Exchange alone traded $169 billion daily in 2013. Global equity markets trade trillions in dollar value annually.

People in financial markets use a framework called “market microstructure” to describe and analyze the way securities trading takes place. There are four dimensions to it: “market structure and design, price formation and discovery, transaction cost and timing cost, and information and disclosure.”

Let’s compare the way US equity markets and the RFP process work at a high level. They both involve the exchange of goods and services of varying complexity in a compliance-intensive environment.

The American system is referred to as the National Market System, or “NMS.” It includes individual stock exchanges, a “central securities depositary for book-entry transfers,” a “depositary nominee,” a “Proxy Ballot processing organization,” “intraday clearing corporations,” and “facilities which operate the national price quotation system.” Consider some of these in turn.

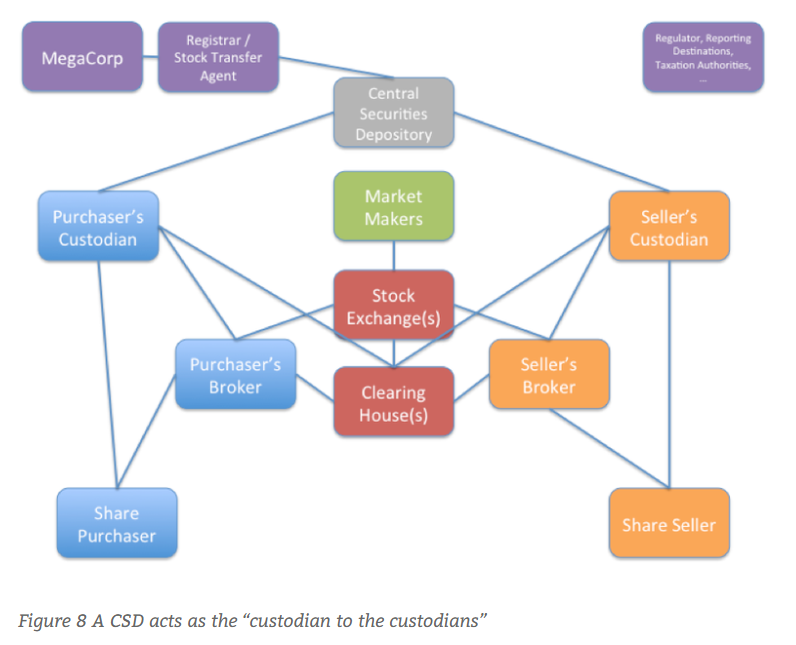

Here is a graphical depiction of a market system.

If you were looking to purchase stock of a specific company, how would you do it?

In the beginning, you would have to figure out who owns the stock you want to buy (and who themselves also wants to sell), somehow communicate to them that you’re in the market to trade, and then figure out a way to agree upon a mutually agreed upon price. This is phenomenally difficult.

So, marketplaces, called stock exchanges, emerged as a place to facilitate trading. Today, in the US, there are dozens of exchanges from the mammoths like the New York Stock Exchange and the Nasdaq to regional exchanges to niche exchanges to dark pools that facilitate exchange between large buyers and sellers. Securities may trade on more than one exchange. There is one place where investors can see all the trades across every exchange: the consolidated tape.

Just to keep things simple, let’s ignore the issue of stock in public offerings and talk about shares that are listed already for secondary trading. These securities trade as an auction that runs continuously from the open to the close of daily activity.

Now that we’re using an exchange, the buyer of the shares tells her broker that she wants to buy 1,000 shares of XYZ Corporation Common Shares. The broker is an agent who helps to arrange the transaction, an intermediary familiar with the process of buying and selling equities on the exchange and someone who is connected to other brokers on the exchange.

Ideally, there is some other seller who tells their broker that they would like to list some number of XYZ shares, say 10,000, for sale, but there may not be another willing seller immediately.

Market makers provide a market in the stock so that our buyer can execute their transaction in a timely manner, by quoting a price at which they would sell her the 1,000 shares of XYZ. The market maker may carry an inventory around which they trade with their position in XYZ stock going up and down through the day, or they may borrow the stock and sell it short, looking to close out the stock loan by purchasing the stock at a lower price later in the day. Why would they do this? Market makers hope to earn profits as a principal, risking their own capital, to capture the bid/offer spread and to earn proprietary trading profits by buying low and selling high.

When our buyer purchases the stock, she must deliver the cash consideration and the seller must deliver the shares. If the stock was priced at $7.00 per share, this would be $7,000 for 1,000 shares. Imagine that the shares are still in paper form. How does she know that she will get the shares if she puts up her money? The broker doesn’t guarantee delivery; they’re just agents.

How does she send the money and receive the stock? Where will she store the shares?

What happens if XYZ issues a dividend? How do they know to give her the money?

What is the risk that someone along the way stiffs her by not fulfilling their end of the bargain?

The exchange reports a negotiated transaction between a buyer and a seller (buyer buys 1,000 shares at $7.00 per share from the seller) to something called a clearinghouse who then acts as the counterparty for each. The buyer purchases the shares from the clearinghouse; the seller sells the shares to the clearinghouse.

Neither one is exposed to the credit risk of anyone other than the clearinghouse. For example, if the seller fails to deliver the shares, then the clearinghouse will buy the shares and deliver them to the buyer, effectively ensuring the transaction proceed, using the clearinghouse’s capital that it has accumulated over time from the profits generated by the fees it charges buyers and sellers.

The clearinghouse deals with the paperwork involved with the transaction and communicates with something called a custodian for each of the buyer and the seller. The buyer’s custodian receives the stock, records her ownership of the stock, and processes other corporate transactions like dividends. The seller’s custodian receives the cash and increases the value of her account.

There are other players here, but they are peripheral to the comparison with the RFP process. These include the company registrar, an entity responsible to the issuer for keeping tabs on who owns XYZ shares, and the “custodian to the custodians” or central securities depository that provides custody services to the custodians.

Pricing is determined by supply and demand in an auction format. Exchanges compile order books that change continuously, listing, for each security, who wants to buy and who wants to sell and at what price. In our example, there may be a large buyer who is willing to buy 1,000,000 shares of XYZ at $6.82 per share, for example, or there may be sellers of the stock at $7.03. These are called limit orders. Price discovery comes out of transactions as market participants adjust the prices at which they are willing to buy or sell a security.

Transactions cost includes the fees paid by the buyers and/or the sellers to execute a transaction, to be sure.

In the context of market microstructure analysis, it refers to elements such as the size of the bid/offer spread and the ability to execute a large transaction without affecting the price significantly. This comes down to liquidity. In a deep market, with plenty of buyers and sellers on both sides of the order book, it is easy to move large amounts of shares without affecting the price. In thin markets that lack depth on one or both sides of the order book, a large transaction can lead to a very large adverse change in price.

Timing costs refer to the length of time it takes to execute a specific transaction. In illiquid markets, trading a large block can take days or weeks.

The rules of the market can impact transactions costs. Some markets have designated market makers who are required to provide liquidity by showing a price into the order book as a way of deepening the order book. These tend to dampen transactions costs over time when compared to exchanges that permit market makers to withdraw.

Finally, US equity markets tend to operate transparently when it comes to market activity. Everyone can see the prices of transactions that happen in real time (if they pay a fee for data access), or they can see this data typically with a short lag. US equity markets mandate significant disclosure of things other than price, including the activity of insiders, corporate activity, etc. As well, US regulators require issuers to provide substantial and meaningful corporate information to investors so that they can understand the risks they are undertaking.

Some estimate that corporations “spend between 45% and 65% of their sales revenue on procurement.” In the US alone, that translates to upwards of $7 trillion in annual third-party spending. Of course, here, procurement includes strategic sourcing using an RFP process, as well as purchasing out of buyer-specific punch-out catalogs.

Yet, using a market microstructure lens, the process looks remarkably backwards when compared to the way financial markets operate.

There is no equivalent to the National Market System that ties buyer and supplier organizations with a common framework of tools and context.

Every buyer is out there looking for suppliers individually. It is as if every buyer is running its own exchange.

Every one of these private exchanges (and there are millions of them) has its own idiosyncratic set of procedures for qualifying a supplier as a participant (“vendor administration”) and for notifying suppliers of transactions that take place, not continuously, but discretely.

For government buyers, they must post their purchasing intentions on a site like FedBizOpps in a jumbled word cloud of widely different opportunities and hope that suppliers pick out relevant projects despite the possibility of what we have called Type I and Type II errors.

Corporate buyers identify potential suppliers and email them the RFPs; the trick there is to get on the buyer’s short list, otherwise you will never find out they are in the market.

Buyers of all types struggle to attract suppliers who are willing to navigate the bureaucracy, which differs from buyer to buyer and which is often painfully duplicative.

There is no central clearinghouse for vendor management, or for the proper filtering of opportunities so that suppliers see only relevant prospects in real-time. There are services that claim to broker this opportunity data, sending daily lists of new RFP postings, but their historical unreliability means practically that suppliers use them as a supplementary service and nothing more.

There is no custodian for contracts. Buyers may have to manage thousands of small suppliers depending on the vertical category. For example, services like corporate training are characterized by many small vendors.

There is no clearinghouse for risk, so buyers and suppliers bear counterparty risk directly. Nor is there readily available information about supplier risk. This may be unavoidable, but it means that understanding counterparty risk is vital. Does the supplier have the capabilities to do what they say they can do? Does the supplier have the capacity to execute in the scale they promise? Do the suppliers have the financial wherewithal to survive to service long-lived contracts? How have suppliers behaved in the past? Do buyers pay on time? Do buyers understand their problems, or will they purchase the wrong solution and blame the supplier?

There is no central tape where buyers and suppliers can see related transactions including price information and other data related to the contracts. Price discovery exists in silos with liquidity that is often restricted by the conditions buyers impose upon suppliers, all in the name of risk management.

Transactions costs are high, both in terms of the administrative expense endured by buyers and suppliers in corporate procurement, but also in terms of the time it takes to execute a transaction. It is not unusual to hear stories, especially in government, of technology purchases that take so long to execute the item is obsolete by the time the transaction is finished (and with a price that is materially higher than the current price for hedonically controlled equivalents because of the natural deflation in technology prices).

EdgeworthBox is a platform that was designed specifically to bring features of financial markets to the corporate RFP process. Sitting as a layer on top of the internal systems (or, in the context of this article, the corporate exchanges), we act as a type of national market system, bringing tools that transform the underlying RFP business model for the 21st century. We include features like a central clearinghouse for administration, a central clearinghouse for data and transparency, and social networking tools including messaging within and outside of buyer and supplier organizations to bring scalable supplier participation, data from government procurement that acts like a central tape combined with internal, private data for better company-wide collaboration, and the ability to collaborate within and outside of organizations. We call it network-based sourcing™.

Let’s schedule a consultation. We’d love to talk to you about RFPs. The doctor is in. Reach out to us at sales@edgeworthbox.com.