We live in a connected world. Personally, we’re part of families, companies, and social networks. Our organizations are tied together inextricably. We have suppliers, customers, partners, regulators, tax collectors, and communities. Everything exists in connection to nature and in the context of technology.

2020 is a year in which a virus spread exponentially: slowly, slowly, then quickly. This led governments to shutdown vast swathes of the global economy and to lockdown whole populations, only to see them react strongly to the spark of social injustice in a mid-sized city in the Midwestern United States.

Risk is the quantifiable assessment of both the likelihood of something happening, as well as its impact. Uncertainty in the Knightian sense comes from something that could happen but for which quantification is not possible. Perhaps it is because we cannot imagine the event ever happening, so we are unaware, or perhaps it is that we cannot comprehend the extent of its influence.

Did anyone have Covid-19 on their bingo cards for 2020? Or rolling protests focused on social justice? If so, did they have a sense for what these scenarios would entail economically?

To manage risk means to take steps that enable us to maximize the benefit from positive outcomes that may or may not happen, while minimizing the cost of negative outcomes that may or may not happen, allocating resources based on likelihood and impact.

As a procurement expert or head of operations, you might think that in planning your supply chain that you are engaged in a deterministic exercise (for the most part). Investors might agree with you that your function is to optimize production, extracting efficiencies and streamlining wherever possible.

If that’s what you think, you are wrong and 2020 is the proof of your error.

According to ISO 31000, risk management is “intended to establish the context, communicate and consult with stakeholders, and identify, analyze, evaluate, treat, monitor, record, report, and review risk.”

But there is one important nuance that this definition fails to emphasize: interdependence. We cannot assume that individual risks are independent. In fact, we know in many cases that if risk A is realized then that affects the likelihood of risk B and risk C, along with the magnitude of their effects. Realization of A may dampen the effect of B or it may amplify the consequences of C.

For example, if there is an epidemic in China like Covid-19, then local manufacturing capacity will fall, authorities will restrict travel, etc.

Getting interdependence correct is difficult.

For example, the World Economic Forum is cognizant of interdependence and they try to explore interdependence in their annual risk reports. Notably, the WEF report for 2020 both discounted the likelihood and the impact of infectious disease.

What did they get wrong?

There is an excellent article in the Journal of Network Theory in Finance that discusses this. But it is their broader conclusion about how to get interdependence right that has lessons for how procurement teams can do a much better job.

The WEF asked 750 experts about pairs of risks, specifically whether they were linked and what weights the assessors would attach to those links.

According to the JNTF article, there were two key flaws. One, the experts were limited to two risks at a time. This limited the number of connections between risks to those pairs that were in the survey. There was also no context to the link. Was it a causal relationship? Or were the risks linked because they fit the same label?

The alternative approach that the JNTF team took was to present respondents with a set of 143 risks to describe using 24 unique tags.

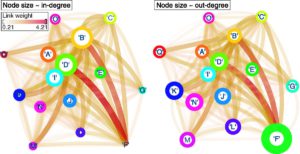

The results here were a network of risks defined by their statistical similarity into five clusters. Each cluster represents risks that were densely connected to one another, with loose connections to risks in other clusters.

As opposed to the typical method of risk management in which people think about risks with an organizational perspective (strategic risks, regulatory risks, market price risk, etc.), here the description of the risks led to a bottoms-up classification.

With this new bottoms-up approach, it is possible that risks that would not appear in the same grouping in a traditional scheme might be actually quite similar. That is, top-down labeling would bias the risk assessment, creating blind spots.

Risk similarity is important because of what it means for identifying what the authors call emerging risks: “a material, previously unconsidered risk or changing risk factor that has the potential to significantly alter the firm’s risk profile.”

It is risk similarity that helps us quantify (on a dynamic basis) the cascading effects in which one risk materializes, leading to the realization of other similar events, which may dampen or amplify the overall systemic effect.

One way to understand this is to think in terms of Facebook. Your network is a set of points, with every person represented by a point. Some of those people are friends from school, others are parents from your child’s school, or former work colleagues. Within those clusters of friends, some have more influence than others. Tell someone a piece of news and it may spread like wildfire, or not at all.

Applying this to corporate procurement, we could also think of networks-of-networks in which each point in the meta-network is a firm within which there is a network of risk factors of clustered similarity.

We can imagine the cascading effects of an event that affects firm A transmitted through its links to other firms in proportion to the weights of the inter-firm linkages in the network-of-networks.

Ideally, a risk analysis would be able to identify different types of firms with similar or offsetting risk profiles in the network-of-networks who could collaborate in such a way as to improve outcomes for all parties.

How do we incorporate this into strategic sourcing?

First, strategic sourcing needs to be seen to be a risk management function. The historical approach of optimizing for lowest cost has to go. In the limit, this can manifest itself in the act of concentrating purchases with sole sourcing to get scale pricing. But, generally, optimizing for price tends to obscure the interaction of other risk factors and their attendant weights in the network of risks, leading to massive cascading systemic risk.

Second, there needs to be a bottoms-up approach to classifying risk. RFP design should focus on surfacing the information that generates an organic clustering of risk factors instead of the current approach using top-down labeling to assess risks.

Third, procurement departments need to work with others within the organization including staff from finance, marketing, operations, and product to assess risk.

Fourth, there needs to be more collaboration between buyers and suppliers, but potentially also different groups of buyers to take steps to mitigate the downside and shape overall risk profiles.

Strategic sourcing today resembles financial risk management twenty-five years ago. We can apply lessons from how finance has evolved to accelerate the modernization of procurement.

EdgeworthBox is a platform for strategic sourcing, generally, that enables this more holistic approach. We do so as a layer that complements existing procurement infrastructure, so that buyers can execute an RFP cycle that leads to more supplier proposals, when an RFP is appropriate and also develop relationships with suppliers that are suited to a broader context. All without changing the infrastructure they have invested so much in building to date. Give us a shout. Or take us for a free spin.